MySQL implements the BIT data type differently in different versions, and the behavior is not what one might expect. In this article I’ll explain how MySQL’s behavior has changed over time, what strange things can happen as a result, and how to understand and work around display issues. I’ll tell you about a serious bug I’ve found, and discuss differences in the BIT data type between MySQL and Microsoft SQL Server.

History

MySQL has supported the BIT data type for a long time, but only as a synonym for TINYINT(1) until version 5.0.3. Once the column was created, MySQL no longer knew it had been created with BIT columns.

In version 5.0.3 a native BIT data type was introduced for MyISAM, and shortly thereafter for other storage engines as well. This type behaves very differently from TINYINT.

Changed behavior

The old data type behaved just like the small integer value it really was, with a range from -128 to 127. The new data type is a totally different animal. It’s not a single bit. It’s a fixed-width “bit-field value,” which can be from 1 to 64 bits wide. This means it doesn’t store a single BIT value; it’s something akin to the ENUM and SETtypes. The data seems to be stored as a BINARY value, even though the documentation lists it as a “numeric type,” in the same category as the other numeric types. The data isn’t treated the same as a numeric value in queries, however. Comparisons to numeric values don’t always work as expected.

This change in behavior means it’s not safe to use the BIT type in earlier versions and assume upgrades will go smoothly.

Display issues

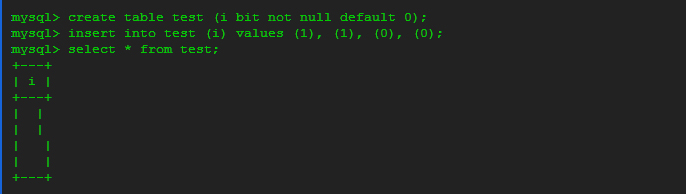

The client libraries, including the command-line client and all the GUI clients I’ve seen, don’t seem to know how to handle BIT values. They don’t display them as a series of ones and zeroes. For instance, the following code even breaks the alignment of the command-line output!

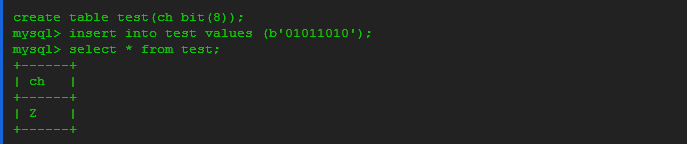

As I mentioned above, the data seems to be stored internally, and transmitted through the client libraries, as aBINARY value, which is actually a string type in MySQL. How it displays depends on the width of the column. For example, if the column is 32 bits wide, it is treated as CHAR(4). If it’s 8 bits wide, it is treated as CHAR(1):

To display the value as an integer, it has to be cast to another type. One way to do this is add 0 to the value:select ch + 0 from test;. Another way is select cast(ch as unsigned) from test;

Display width seems to be related to value with BIT, in contrast to what the manual’s section on Overview of Numeric Types states: “Display width is unrelated to the storage size or range of values a type can contain.” It appears that a field of size M can only store M bits, so it’s the storage size, not the display size, that’s affected. As I mentioned, bit values don’t display as ones and zeroes anyway, so it makes no sense to say an 8-bit wide column “displays with a width of 8.” It doesn’t display 8 bits, it stores 8 bits. In fact, insertingb'100000000' into the table I defined above will store the value 255, demonstrating that the actual value has a maximum capacity of 8 bits. Any bits not set explicitly to 1 are set to 0, so values are left-padded with zeroes (the most significant bits are zeroes).

Bugs

I’ve discovered some very strange bugs with BIT columns in MySQL. The issue I noticed was a LEFT OUTER JOIN failing when it should have succeeded. I discovered a combination of factors could cause the bug to appear and vanish. For example, the join will succeed or fail depending on combinations of these factors:

- the presence of an additional column, not involved in the query at all

- the presence of additional rows which don’t match in the join

- the order of columns in the table

- the presence of an additional tautology in the join clause

I’ve filed a bug with MySQL about the issues I found, including a script which demonstrates several ways to trigger the bug.

Why use it?

Given the problems I’ve mentioned, I recommend avoiding it entirely. It provides nothing that’s not already possible with standard numeric types and adds a lot of confusion.

Differences from Microsoft SQL Server

Microsoft SQL Server also provides a BIT data type. However, it’s completely different; it’s a single-bit column. Internally, it is stored as a single bit within an integer data type. As successive BIT columns are added to a table, SQL Server packs them together behind the scenes. This is equivalent to doing bitmask operations on a single column (my previous employer loved bitmask columns!), but it allows the bits to be named explicitly, avoiding the need to pass around named constants (or embed magic numbers) and deal with bitwise arithmetic.

Pros and cons of bitmask columns

Bitmask columns (an integer within which each bit is retrieved and set via bitwise arithmetic) can be extremely handy. They’re a very compact way to pack true/false values together for efficient storage. They can also facilitate certain types of queries; for example, “if any value is set” queries become simple. I’ve used them in ACLs stored in a database, for instance. Certain types of problems are just easy to solve with bitwise arithmetic, and for those problems, creating an integer column and declaring “bit 5 is whether the value is [something]” makes a lot of sense.

On the negative side, bitmask columns can be hard to use. For one thing, they’re hard to understand. Without the documentation that says which bit means what, they’re pretty much useless. SQL Server avoids this and the other problems I’ll name by treating each bit as a separate column and naming it, but that’s only if you use that facility, which my previous employer didn’t. Bitwise arithmetic can also be pretty tricky to write, and even harder to read.

Magic numbers in queries are just as meaningless as a column named bitcolumn1. Declaring and passing around constants to name the magic numbers is a nice thought, but it’s error-prone and it’s extra work. Creating a table to define the bits can be quasi-helpful as well, unless (as often happened at my previous employer) you can’t find the table, or the column is named such that you can’t tell which table defines the values for which column, or the table’s values don’t make any sense for bitwise arithmetic.

Bitmask columns are also not index-friendly, so querying against them isn’t optimal. Of course, any column with only two values is useless to an index anyway, so this is no worse, performance-wise than storing the yes/no values in columns by themselves. Since there’s fewer data to examine, it can actually be more efficient.